The swastika – a symbol beyond barbarism

by Thomas Maier

Around the year 1900, when the explosive geopolitical upheavals on the horizon could already be foreseen – nowadays our crises pale in comparison – the swastika was hugely fashionable. At the end of the century it became a ‹lucky charm›, following its interpretation of the Russian Ruling Family, and it even graced the family’s limousine as the hood ornament. Its use as an icon was more comparable to that of the four-leaf clover today –∫although preserving a bit more of its archaic character. The Russian Tsarina’s daughter Tatjana stitched the swastika onto her mother’s diary in the wee hours of the dawn of 1918. At that point the family had already been incarcerated by the Bolsheviks, making Tatjana’s action the first real politicization of the swastika and the first glimpse at the ‹barbaric› career it would go on to have. This new connotation was further manifested by the behaviour of her mother, the last Russian empress, Alexandra Feodorovna: she drew the swastika with the date of their arrival into a window frame of the building she and her family were being kept in. It was the first time the antagonism between another symbol, the Red Star, which would grew to represent the annihilation of aristocracy and bourgeoisie, and the swastika, materialized. At the end, the swastika in the window frame brought the family no fortune: in the summer of 1918 they were liquidated and thrown alive into a pit. Three days later the pit was filled in with dirt, silencing their last lingering pleas for life.

1

1

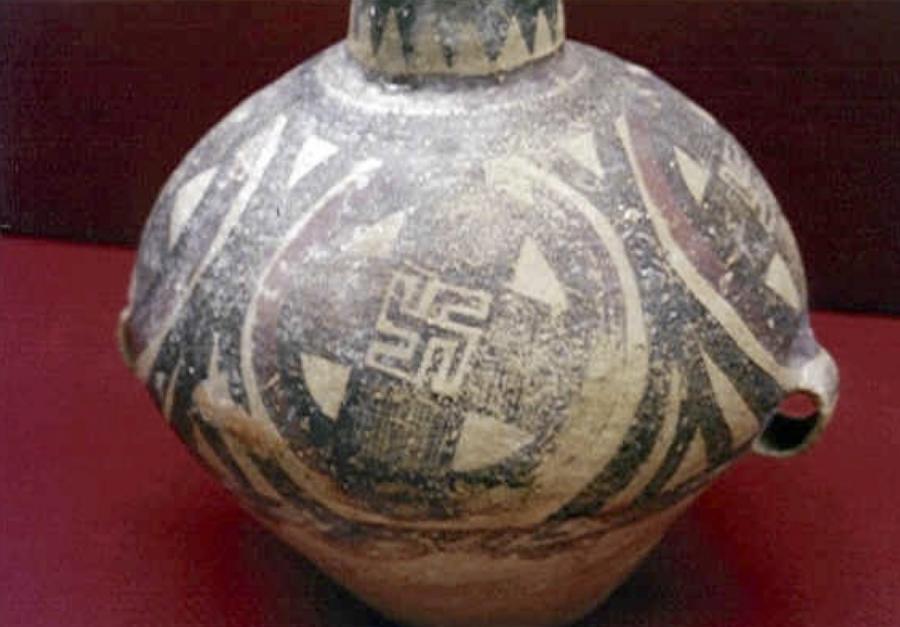

But the actual story of the swastika goes far beyond such appearances in modern history. It had always been an important symbol of Japanese and Korean Buddhism, where one finds it engraved in temples and other religious buildings. Hinduism and the Indonesian culture cherish the symbol as well. In the ancient Indian language Sanskrit, ‹swastika› means ‹it will turn good› (from ‹su›=good, ‹vasti›=to be). In its ancient use, the symbol wanders from representing goodness, harmony, peace, and life to the gods, the sun, or a star to the four winds as the cardinal directions. There are Middle Neolithic ceramic vessels created more than a thousand years before the earliest of the Chinese states arose. The swastika is found in the art of the vast majority of cultures in the Northern Hemisphere: for example it appears in ancient Greece, among the early Jews, and even in mosaics in Christian churches in the Italian city of Ravenna.

The more the world faced down the abysmal events in the beginning of the 20th century, the first being the eruption of World War I, the swastika was proliferated as a hopeful sign bringing good luck. But after the liquidation of the Tsarina’s Family, events accelerated very quickly: the swastika had already been a sign used by smaller ethno-nationalistic, anti-Semitic, and anti-Communist groups, who connected the symbol back to ancient Aryan warriors. And it was already featured as decoration in combats in 1919, when the Bavarian Council Republic, a short-lived Socialist state in Bavaria, was being broken up: the fear towards Communist resistance and attacks created the swastika’s space of resonance for Nationalist sects. In 1920, the author Joseph Roth noted that the Red Army can’t invade East Prussia, because ‹the Swastika is far too strong› there. In this very year, Adolf Hitler used the symbol for the first time as the emblem for the National Socialist German Workers’ Party. From then on it was the symbol of the war against ‹financial Judaism› and for the ‹Aryan race›.

That the swastika is today taboo is an interesting causality resulting from this recent history: while in the United States the swastika, as well as the Communist symbol, are allowed with only minor protections, they are both prohibited in Eastern European countries like Hungary. When German politicians wanted to introduce an EU-wide prohibition of the swastika, the effort was stopped by the Czech Republic, arguing that they would only approve of the ban if it would be applied to the Communist symbols as well2.

3

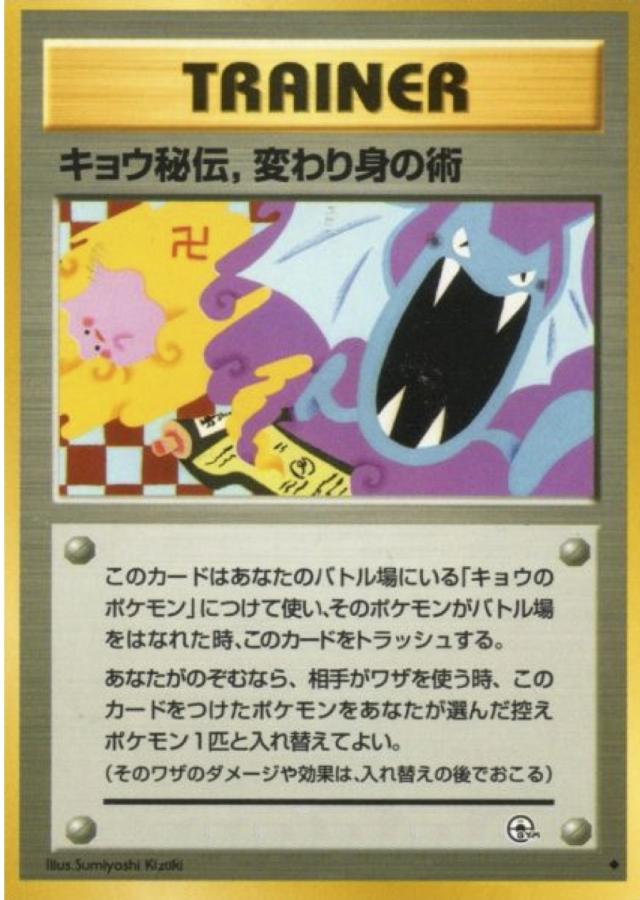

Controversy over the swastika is also seen in pop culture, such as when a fashion label recently withdrew their catalogs due to the use of the symbol on jacket buttons. Seventy years after the end of the Nazi regime, the most taboo symbol in the history of mankind is more under siege than ever: even crossed out swastikas from anti-fascist merchandisers can be subjects of penal procedures in Germany. This neo-iconoclasm begs the question: what would be the removal of the swastika’s loss to culture? The loss to visual culture might be easy to overcome. The more important stakes are in play where the swastika is being decisively withdrawn from the historical narration. In the ruins of Troy, archaeologists found thousands of small ceramic figures with swastikas on them. If you look at books about Trojan excavations, you can find all kinds of sculptures, but almost never those with the swastikas upon them. With this censure, the central tenet of historiography, that is, comprehending a full, accurate, and objective narration of history, is being undermined.

Paradoxically, it is the trial of the swastika, which stands to bring barbarism to its utmost potential: the bestialization of history. And this corruption creates a new space of resonance around the symbol for a narration outside of the canonical one. The swastika is the troubled sign that got mixed up in the strongest geopolitical antagonism of the last 150 years: such a paradigmatic turn from a religious and esoteric sign to a profane symbol for good luck, and then ultimately to the signature of cruelty and the politics of annihilation has been suffered by no other symbol in recent history that gravely. While trying to stand against the horrific history behind the swastika through its censure, the full truth – its thousands-of-years space of resonance – is what is missed out on. And that is the truly barbaric event: history being incompletely told, forgetting its cultural, ethical, and semiotic narrations, and finally giving in to an interpretation that creates a vastly uncontrolled vacuum that can be filled by all kinds of dangerous, lopsided interpretations.

More imagery of swastikas: http://www.archaeometry.org/swastika.htm

Thomas Maier is based in Karlsruhe, Germany.

- 1. 5000-4000 B.C.: Central Mediterranean. Photo by David Cornberg, taken in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan.

- 2. As opposed to the former states of the Eastern Bloc, the so-called West shared with the Soviet Union at least one belief: Communism’s descent from Enlightenment and its drive to enable a progressive, emancipatory society. And that is the contrary to a ‹barbaric› society. One might be more eager to believe in Communism’s ‹well-meaning intentions› at bottom. That is why the views on Communism are today still closer to society’s general conscience than National Socialism that is being interpreted as reactionary, anti-modern and therefore ‹barbaric›.

- 3. Japanese Pokémon card (swastika, top left). Soon after it was released in the US, the distribution was halted due to use of the swastika. Photo by Nintendo, Wizards of the Coast, Media Factory, AMIGO Spiel + Freizeiti GmbH, Pokémon Illustration.

you've got barbarians

you've got barbarians